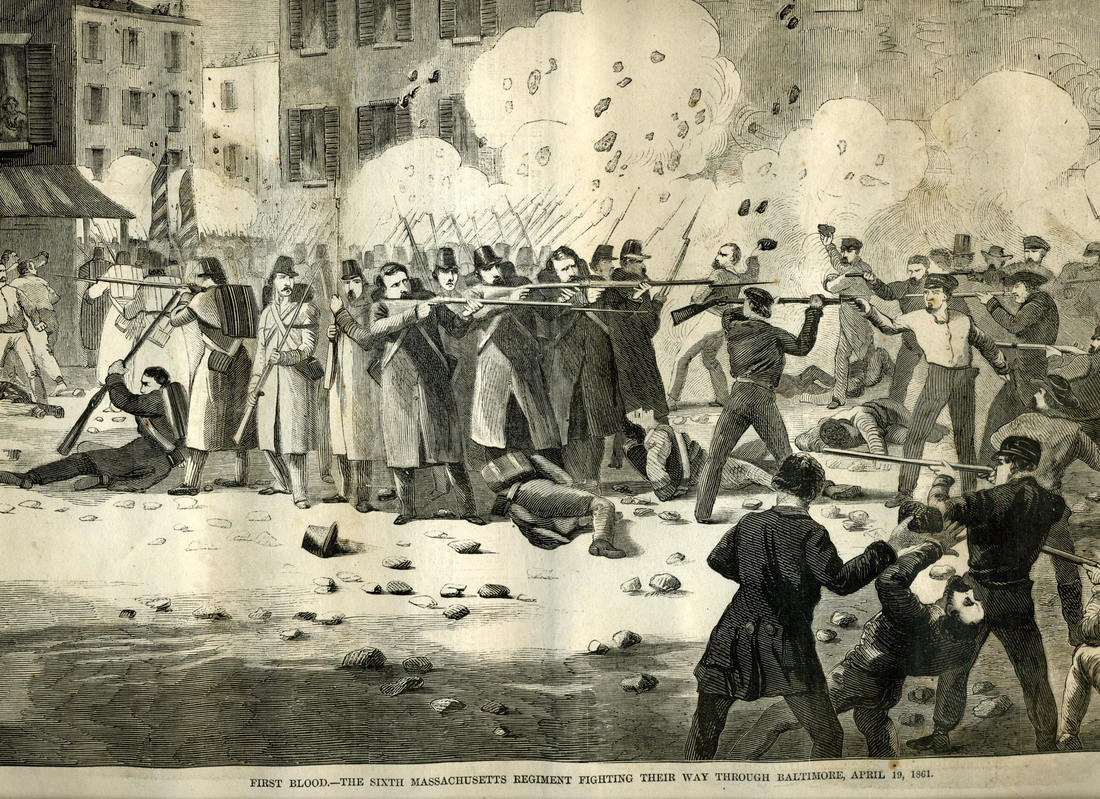

"You will undoubtedly be insulted, abused, and, perhaps, assaulted, to which you must pay no attention whatever, but march with your faces to the front, and pay no attention to the mob, even if they throw stones, bricks, or other missiles; but if you are fired upon and any one of you is hit, your officers will order you to fire. Do not fire into any promiscuous crowds, but select, any man whom you may see aiming at you, and be sure you drop him."

Mayor George William Brown

Mayor George William Brown “The despot's heel is on thy shore,

Maryland, my Maryland!

His torch is at thy temple door,

Maryland, my Maryland!

Avenge the patriotic gore

That flecked the streets of Baltimore,

And be the battle queen of yore,

Maryland! My Maryland!

Dear Mother! burst the tyrant's chain,

Maryland, my Maryland!

Virginia should not call in vain,

Maryland, my Maryland!

She meets her sisters on the plain-

"Sic semper!" 'tis the proud refrain

That baffles minions back amain,

Maryland! My Maryland!

I hear the distant thunder-hum,

Maryland, my Maryland!

The Old Line's bugle, fife, and drum,

Maryland, my Maryland!

She is not dead, nor deaf, nor dumb-

Huzza! she spurns the Northern scum!

She breathes! she burns! she'll come! she'll come!

Maryland! My Maryland!”

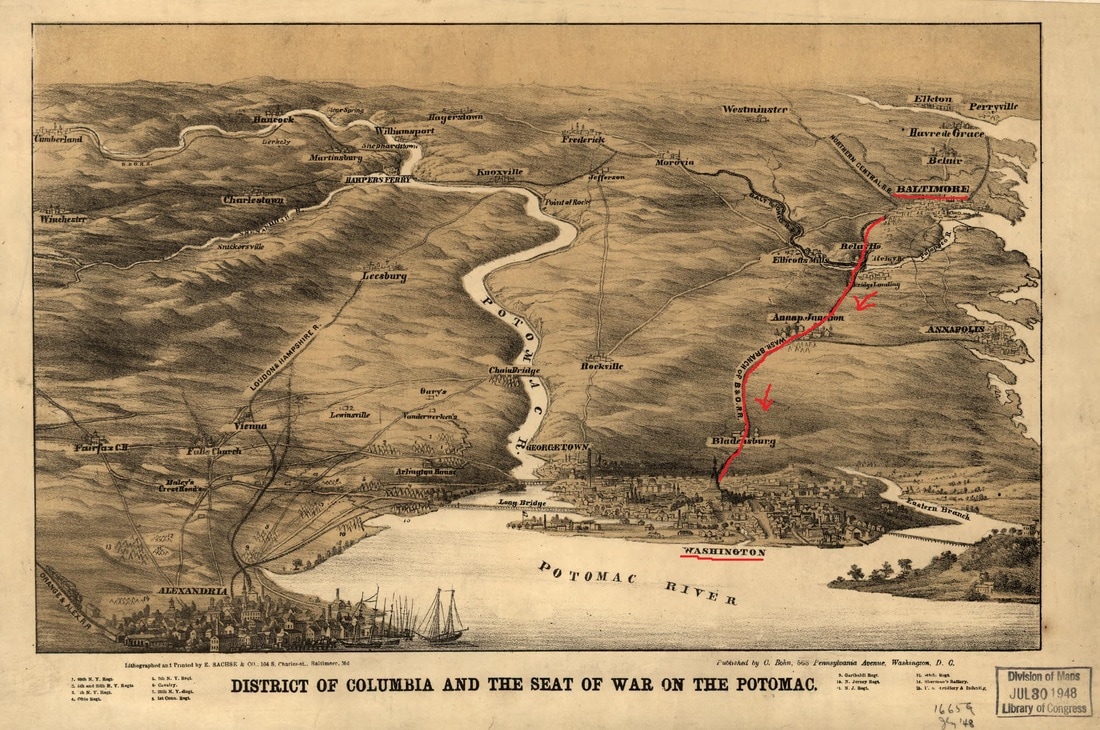

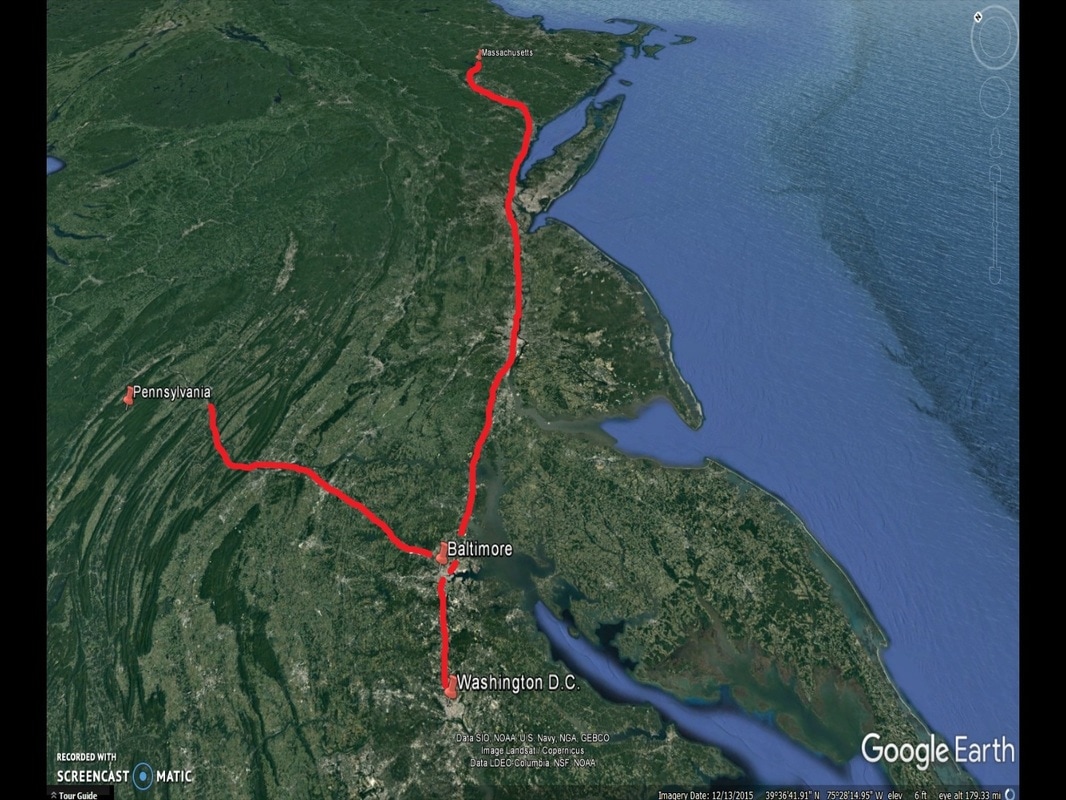

"When I looked out in the morning, I could not help being struck by an odd and not pleasant coincidence. On that day forty-seven years before my grandfather, Mr. Francis Scott Key, then prisoner on a British ship, had witnessed the bombardment of Fort McHenry. When on the following morning the hostile fleet drew off, defeated, he wrote the song so long popular throughout the country, the Star Spangled Banner. As I stood upon the very scene of that conflict, I could not but contrast my position with his, forty-seven years before. The flag which he had then so proudly hailed, I saw waving at the same place over the victims of as vulgar and brutal a despotism as modern times have witnessed."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed